Viewing the work of Naomi White is like seeing the world through the eyes of an observant pedestrian. One who walks quietly through suburban streets, parks, farmlands and forests, and encounters moments of verdant glory that often occur in the most commonplace locations.

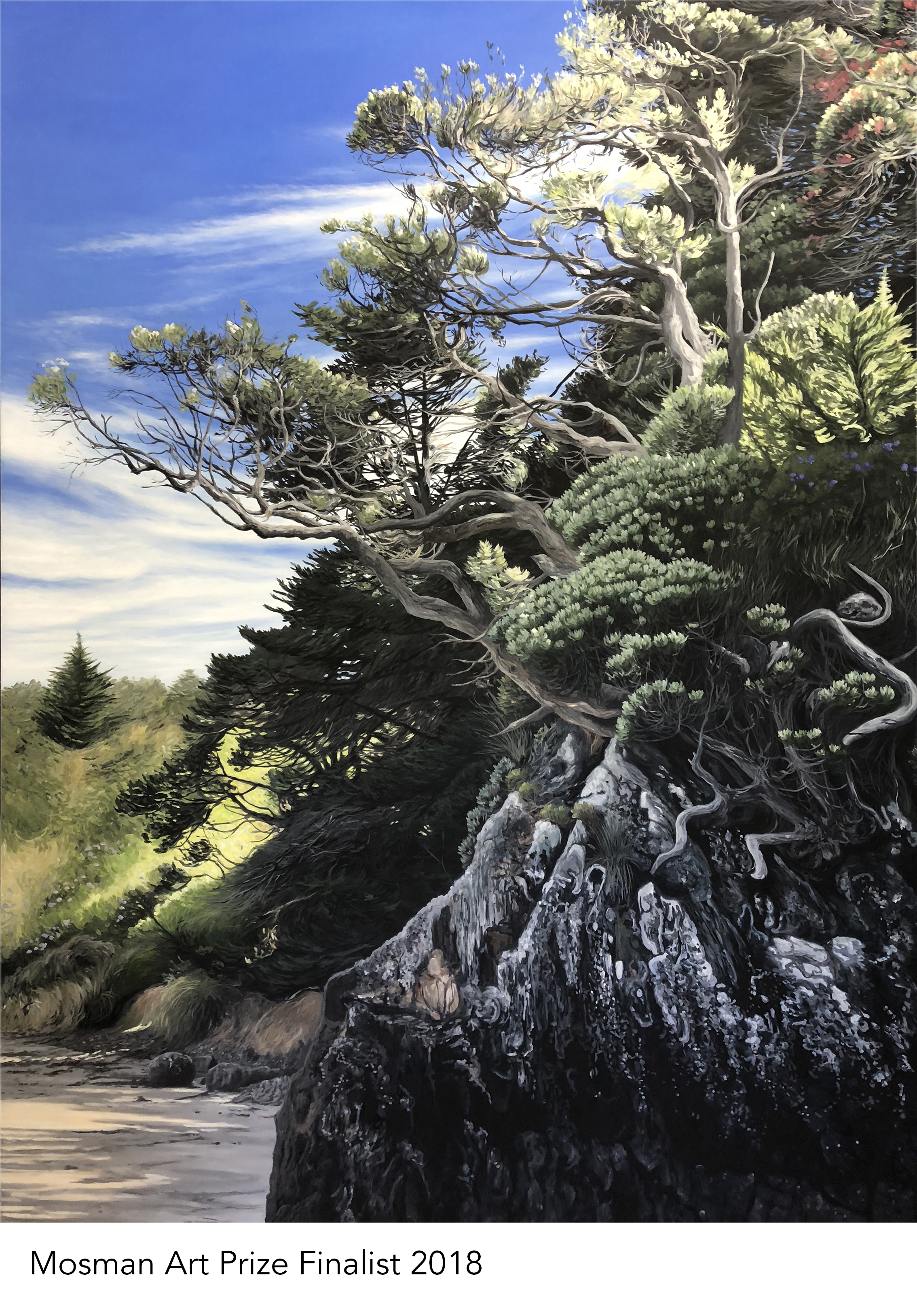

The eye-level of this imaginary wanderer is low, like that of a small child or an animal, but this allows for a greater emphasis to be placed on the blades of grass, branches, and leaf litter that usually pass unnoticed underfoot. These tiny elements are given exquisite attention, as with fine brushstrokes and delicate mark-making White renders them with empirical accuracy.

This worm’s eye view of the world and the almost scientific level of detail that White renders it with is reminiscent of work by early nineteenth century German artists of Dusseldorf Academy. Eugene Von Guerard, the great colonial painter of Australian vistas studied at this progressive school for landscape painting, which was influenced by developments in natural history and biology, and encouraged truth to nature as opposed to idealizing the landscape. Such work displays a detailed observation of the natural world, a similar one to that which White applies to describe her contemporary surroundings.

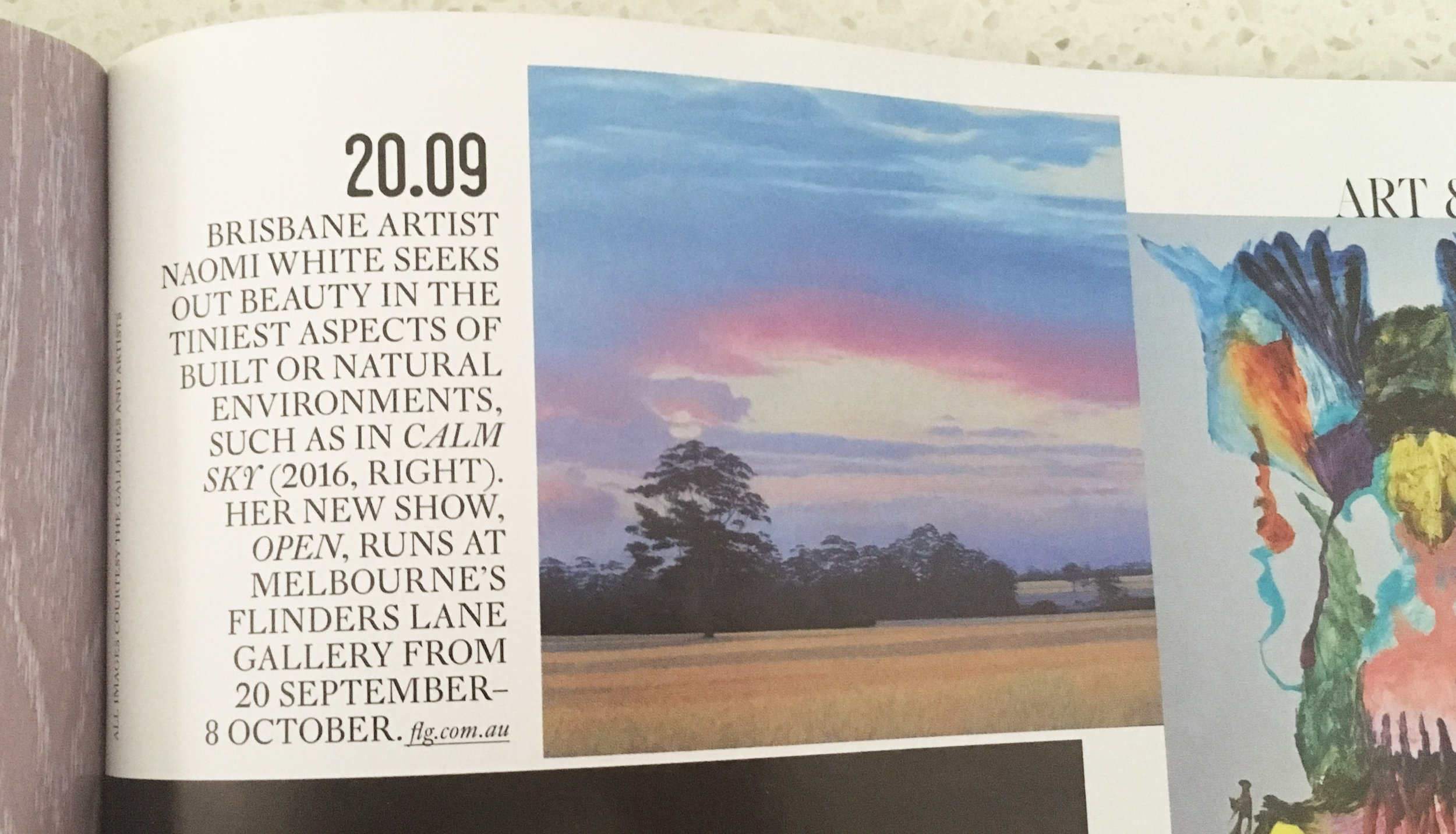

Yet in White’s work this sense of botanical verisimilitude becomes animated beyond pure description, as countless tiny marks coalesce in flowing unison for a poetic effect. Central to her imagery is the depiction of light. All of the various locations she paints, which are often within the vicinity of Brisbane where the artist lives and works, are depicted with a bright, clear light that is uniquely Australian. The artist uses strong sunlight to throw up sharp contrasts as seen in works such as Lost Streets and Hiding. Here swathes of vegetation are illuminated by light, as it travels through the semi-transparent leaves casting them vibrant shades of green. These stand in contrast to the deep, cool shadows they are often depicted against creating a powerful optical effect.

White offsets her joyful rendition of the natural world through including ubiquitous trappings of urban life, contextualizing her work within suburban Australian reality. This is denoted by the presence of municipal council wheelie bins. They appear in a number of works, standing like lonely sentinels in a back lane, a footpath, or even a paddock where they appear strangely dislocated. In all cases they interrupt the otherwise picturesque state of the scene with their ungainly black plastic presence, pointing to the ever-present human footprint on our natural environment.

Yet the most pronounced feature of White’s work is her depiction of the order that emerges from a seemingly random arrangement of individual elements within nature. In Lost Streets the leaves that cascade like a waterfall to engulf the ramshackle fence toward the background of the image, do so with a graceful flow that is reminiscent of the unified movement of a school of fish, or flock of birds. While in Through the Briar, with a characteristically low viewpoint the artist paints numerous entangled branches that rise up rhythmically to be encircled by green vegetation, through which we catch a glimpse of the light blue sky.

It is through the representation of these many tiny natural elements, brought together in a harmonic mass that White shares her personal exultation of the experience of the world around her. All through the slippery medium of oil paint on canvas.